Grounded (Freumhaichte/Wadlu-Gnana). Judith Parrott

An Lanntair, Stornoway: 13 September - 11 October

Grounded is an exhibition of photographic prints, audiovisual, sound and prose, resulting from residencies with Gaelic speaking communities of the Outer Hebrides of Scotland and with Wangkangurru, Arrarnta and Arrernte people of the Central Australian Desert. The exhibition was launched at XX Commonwealth Games, Glasgow 2014.

Follow Judith’s Grounded blog at http://judithparrott.wordpress.com/

Arriving in Steòrnabhagh (Stornoway)

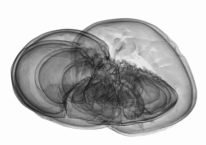

Seagreen. Photo by Judith Parrott

The train rumbles north. Layers of questions that tugged at me in the build up to my journey, peel away like snake skins, left to flutter in the breeze. With every familiar station name: Newtonmore, Kingussie, Aviemore, the air is changing to Highland air; startling yellow Whin is streaking past, and my body relaxes into the rhythm of the train and the dark murky purple of rocks and bracken, carved into the hillsides.

I have changed train at Perth, and again at Inverness. I have caught a bus west to Ullapool, and now, at the end of a long day’s journey from the Isle of Bute, I sit nestled into the ferry, gliding across a silent sea to Steòrnabhagh (Stornoway) on the Isle of Lewis.

Steòrnabhagh settles prettily around the sheltered harbour, with her castle keeping watch across the bay. Though the fishing fleet is not what it was in its heyday, boats still clank and thud against each other, and the soft plop, plop of water at their sides mixes with a rich, salty sea smell which emanates from wood and decks, and from rope and creels piled high on the wharf.

It is, I believe, a 9th Century town, founded by Vikings under the name of Stjórnavágr. But I welcome correction from those who know more about this than me. It is the largest town in Na h-Eileanan Siar (The Western Isles), with a population of just over 6,000 – about a third of the Isle of Lewis’ population.

The population of the Western Isles is around 27,500 and Gaelic is the first language spoken by most of the islands’ population. This is one reason for my journey here, to Na h-Eileanan Siar, on the first stage of my two artist residencies. Following this, the residencies take me in a sweeping arc across the world to the desert regions of Central Australia.

I hope you can join me on these journeys.

Sidney

Photo by Judith Parrott

This story begins on the far northwestern tip of Australia, not today, but four years ago in 2009. It is a place of heat-glazed, brittle land and far away blue. I am in the Northern Cape to work with Thancoupie, primary Thanaquith Elder, at her annual bush camp, which celebrates language and culture with the local children. It is here that the seeds are planted for Grounded; an artistic examination of Australian Aboriginal, and Scottish Gaelic, culture, language, displacement and sense of place.

There follows a sand-trail of people and phone calls, meetings and emails; a pilot project set up on the Isle of Lismore, Scotland and shown to Arrernte Elder MK Turner; a pollinating of ideas which open and close doors like a wave rolling me in to some distant unknown shore. It is three years before I am set down again, in the Gulf Country of Australia, at the small town of Normanton, primarily to run some photography workshops for Flying Arts.

The relative cool of the evening has enticed me out for a walk along its main street, wide and empty, falling to a dusty verge that stretches into the horizon. A stray dog eyes me suspiciously, and the silence is punctuated only by the evening call of lorikeets. In the solitude of the space, I can sense another person on the road and I turn my head to catch his eye. He falls into step beside me.

His name is Sidney and he is one of the traditional owners of the area, the Kukatj, Gkuthaarn and Kurtijar people. “Where are you from?” he asks. He stops in his tracks when I tell him I am from Scotland, a broad smile lighting his face. He wants to know if the story of Braveheart is true. “We have so much in common with the Scottish people”, he says. As we walk and talk, and I take his photo in the burning glow of the setting Australian sun, he asks me to do him a favour. “Will you take this photo to Scotland and tell them I’m your brother?”

Sidney did not know about the concept that had been developing over the last three years, but his words were the deciding factor in its finalisation. With renewed energy I finally ascertained the funding and the partnerships to undertake the project.

These diaries, as they will be posted, represent my time in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland, based on Lewis with the Gaelic Arts Agency, Proiseact nan Ealan, and on Uist with Ceolas, Gaelic Music and Dance School, and also supported by Hi-Arts and Glasgow Life. In Australia the posts will come from Arrernte and Arrarnta Country around Alice Springs; around Longreach; and from Wangkangurru Country around Munga-Thirri National Park (Simpson Desert). My time in Australia is supported by Flying Arts, Vast Arts, italk Library and The Australasian Association of Arts and Cultural Education. Culture 2014 XX Commonwealth Games and Cape Farewell are also supporting production.

The resulting exhibition was shown at Glasgow Merchant City Festival during the Glasgow Commonwealth Games 2014, An Lanntair in Stornoway, and was toured by Flying Arts in Australia.

Follow Judith’s Grounded blog at http://judithparrott.wordpress.com/

About the Artist

Working alongside communities from around the globe, Judith has developed her Place Matters series following her own migration from Scotland to Australia, and consequent exploration of issues around displacement.

She works with the mediums of photography, audiovisual, sound and prose examining the relationships between community and place, the importance of cultural identity, and the resulting personal and environmental wellbeing.

“What I see and present can only be what I am shown by the people I meet and I in no way claim to be able to show every side to the stories in the short time I have available to me. But the taking of photographs and recording of sounds do start conversations, as participants reflect on their sense of place. Much comes out of that process well beyond the taking of a photograph or recording of sound. At the same time the process opens a small window for me to learn something more and share the stories further afield.”