“ … [Kay] has a splinter of glass in his heart, and another in his eye. These must come out or he’ll stay bewitched, and the Snow Queen will keep her hold over him forever!”

“The Snow Queen” – Hans Christian Andersen.

We’ve just spent two days at the Monaco Glacier and there’s a kaleidoscope of ice in my eyes.

I’ve been bewitched. Some mad ice-queen has captured and bewitched me, and I’m afraid of breaking the spell. Possessed, I don’t want to leave this realm of ice and its secrets. I’m afraid of the mind’s desire to process; that it will want to break the connection, spoil the thrill, tell me it was a dream. That on waking, glacier, water, an astonishing cascade of diamonds, sheared and shattered like glass will avalanche down, slipping and melting away the memory forever. In my entranced state I think that if I can hold onto the mysteries of the past two days I may understand secrets and make some useful sense of it all. But I know this is a form of madness. Ice madness.

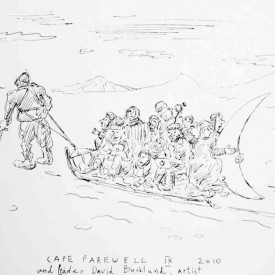

The Monaco Glacier is in the North of Spitsbergen (actually 79 degrees 33mins L 12 degreees 30 minutes E) so that means – to the non-nautical – the edge of the world. The ancients must have thought it the gates to the underworld. At our time of being there on the 22nd and 23rd September, there was no other vessel further north of us barring, perhaps, an icebreaker somewhere in Siberia. It’s hard to describe this remarkable place, but here goes.

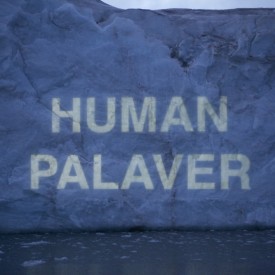

Imagine a theatre, or perhaps a diorama, with a floor of impossibly clear water skimmed by ice. On top float icebergs – barely moving, for there is no wind – amidst mountains, glacier walls, sea and sky; because everything is reflected together here. Every corner is saturated by light, which bounces and flies off every surface. Only the shocking chemical blue of the glacier’s deep interior holds the eye and allows it to dwell. The line between reflection and reality is clear – if you work to find it – but this is a huge jigsaw made of ice printed on mirror.

The glacier walls (for there are four here) are impossible to measure; only a ship or human figure will start to tell you something of its scale. You can sail towards it for three hours and by the time you find yourself sailing beneath it, you are well within its power and grasp, and you feel its danger.

Everything is mirror and prism and facet and glint and sparkle. The eye darts like a minnow in sun-shot waters, and cannot settle. It’s overwhelming; the eye’s appetite becomes ravenous, addicted to the visual clarity. It’s a drug that makes you high, and wears you out with looking. If a scientist could monitor the eye movement as it absorbs and checks, I believe it would outstrip any REM data. Everywhere you look is fascinating, absorbing and so, so sharp. I know no experience where the eye is so undirected and yet so engaged and saturated at every turn. This freedom to look where we please is the great gift of the theatre, unlike film or painting, which strongly direct the eye.

Then there is SOUND.

Sailing under this ice-cliff is dangerous. The risk is brought home to you by sound. At irregular and shocking moments the body jumps to the roar, crack and ensuing deep rumble as some huge ice wall collapses deep within the glacier. Put that fall on the face of the glacier and our tiny boat would vanish without trace. I was on the shore when one of these explosions occurred; a few minutes later, in uncanny silence, the waters were drawn out to sea, and then returned in a long wave along the shore; a baby tsumani, worked by the hand of a God whose heart is ice, who cares not a jot for our attention and survival, but whose domain’s survival is in our hands.

This is the heart of my Arctic journey. Early explorers to this place would feel that they had reached the walls at the edge of the world. I feel I’ve come, quite literally, to the heart of the matter. Now I must try and deal with it. Not solve it, but tackle an understanding of it.

Cape Farewell takes artists to the Arctic in the hope that they may engage with climate change and find a way to communicate its story. It is a complicated story. The media like to pitch one scientist against another in the war of sound bites – but mere sound bites cannot accommodate the necessarily complex scientific information. But the climate change consensus is very clear; 95% of scientists cannot be wrong, although it may well be the case that politicians, who deal in the short term, may not wish to hear the truth of what the scientists say.

So, these glacier walls are the front line – the citadel’s walls. Quite literally the writing is on the wall. They have been some 10,000 years in the making and in some cases just ten years in the melting. The Jacobessenn Glacier in Greenaland is retreating at a jaw-dropping 40 metres a day. These are museums of ice containing 10,000 years of our planetary history in air bubbles, dust and small animals trapped as the ice was laid down. They tell the dark story of the Industrial Revolution and its ongoing impact. They cannot cope with the world we have made. They are coming down and fast.

Does this matter? Well, yes, if we care for the habitat of polar bears, arctic foxes and hundreds of unique species of flower. Yes, if we care that with the melting of the ice glaciers will come great floods and then, after, great drought. Yes, if we care what happens to Bangladesh, Pakistan, Africa and a lot of the poorer world. It may not matter to us in England as we seem at last to be enjoying real winters and real summers, but we will have to spend more of our money in coastal defence and it may lead, in the long term, to much more extreme summers and winters.

Climate change is real. We cannot ignore it. We know our oceans are warming – we have reliable data going back 50 years, some more date going back 100; then we have the glaciers’ 10,000 year story and beyond that the sea-beds with their 80 million years of information. Here in Svalbard, since Cape Farwell’s first trip in 2004, there is visible evidence of glacial retreat. We have witnessed the wonder of these things and also seen the retreat in action. Most shockingly you can hear it. This thing demands our respect and brings us to our senses.

Amundson was the first to walk to the North Pole; in ten years time we will all be alive to witness the last chance to repeat his walk. After that there will be no ice. It will have gone forever.

I’ve seen what I never expected to see and heard what I had not thought to hear. In the days left of this extraordinary voyage I hope this dreaming and this rude awakening will start to prompt a project already seeded in my mind. Probably not an play or an opera but an installation of a kind. It won’t save the world but it may tell others the story.